| The Houston Riots and Camp Logan Mutiny of 1917 |

"Take Texas and go to hell. I don't want to go there anymore in my life. Let's go East and be

treated as people."

-- A note written by a black soldier and found beside a railroad track near Schulenburg.

treated as people."

-- A note written by a black soldier and found beside a railroad track near Schulenburg.

The Houston Riot of 1917, also known as the Camp Logan Mutiny, involved 156 soldiers of the all-black 3rd Battalion, 24th

Infantry – a unit of the famed Buffalo Soldiers. The incident occurred on August 23, 1917, lasting roughly two hours on a hot, rainy

night, and resulted in the deaths of four soldiers and 15 white civilians. The episode has the ignominious distinction of being the only

race riot in U.S. history where more whites then blacks were killed, and it also resulted in both the largest murder trial and the largest

court martial in U.S. history.

Almost four months later, on December 11, 13 black soldiers were summarily hung at a hastily constructed gallows near a shallow

creek on Camp Travis, a National Guard training facility next to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. The men were unceremoniously

buried nearby in graves whose only identification was a number, 1 through 13. Sixty-three other soldiers were given life sentences,

and in September 1918 six more soldiers were hung at the same Camp Travis site.

There was no conclusive evidence or reliable witness testimony that any of the first group of executed men had participated in the

riots. However, the final six men were identified as having fired shots at civilians.

Historians aside, the stories of this bloody and probably avoidable event in Texas history is not well-known throughout the Lone

Star State and curiously not among most Houstonians.

History of the 24th Infantry

African American soldiers had served in the Civil War, heroically, in many cases, such as the 54th Massachusetts’ gallant

performance at Fort Wagner, S.C. upon which the movie “Glory” was based. After the war, on March 3, 1869, several all-black

units were combined into four “colored” regiments – the 24th and 25th infantries, and the 9th and 10th cavalries.

Stationed primarily at remote posts in the southwest frontier, the 24th battled outlaws and hostile Indians and protected settlers,

but served in a wide variety of other duties including building roads, constructing and repairing telegraph lines, and escorting supply

trains and mail coaches.

The unit also saw duty in Cuba, during the Spanish-American War, where they served with Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough

Riders at San Juan Hill, and the 24th would also see duty during the Philippines Revolution. Men from the 24th would be the first to

raise the American flag atop San Juan Hill.

The all-black units acquitted themselves well, so much so that 19 Buffalo Soldiers have been awarded the Congressional Medal of

Honor, including two who served with the 24th Infantry:

from the 600 soldiers, some with families. An editorial in the Salt Lake Tribune newspaper feared drunken black soldiers would

attack “the best people of the city.” In a rebuttal letter to the Tribune, a 24th soldier wrote the men had "enlisted to uphold the

honor and dignity of their country as their fathers enlisted to found and preserve it." He also said, the men "object to being classed

as lawless barbarians. We were men before we were soldiers....We ask the people of Salt Lake to treat us as such."

And slowly but surely they would, after seeing how the soldiers comported themselves, as they joined or formed fraternal

organizations, and their chaplain, Allen Allensworth, one of only two African-American chaplains in the Army, was a popular

speaker at local churches and social events. Black and white crowds cheered for the 24th’s band and baseball teams. As the soldiers

boarded trains for duty in Cuba, whites gave them a fond farewell and expressed they would be welcomed back.

Even the Tribune acknowledged the men's general good behavior and professionalism: “By their actions these African-American

soldiers gained a measure of respect and admiration from the larger white society that was generally denied to black civilians.”

After Cuba and three tours in the Philippines, the 24th guarded supply lines in Columbus, N.M. during Gen. John “Black Jack”

Pershing’s pursuit of Pancho Villa from March 14, 1916 to February 7, 1917.

The next stop for the 24th would be Houston.

Texas fights

Some of the earliest African American soldiers in the West served in Texas, and the 24th was sent to the state at a time when the

area was considered a "soldier's paradise," with nice weather, beautiful rivers with plentiful fishing, and grassy plains that yielded

game for hunting.

While Texas might have been a paradise for soldiers and outdoorsmen, it could be a nightmare for blacks in uniform. Violence

involving black soldiers in the state was common throughout the first quarter of the 20th century. There were confrontations, most

called “riots,” with white civilians at several stops, including the madness in Brownsville at Fort Brown where the entire 25th

Infantry First Battalion was discharged without honor by President Roosevelt as a result of the Brownsville “raid.”

The soldiers were accused of conspiring to withhold evidence and identify the shooters of a white bartender and the wounding of a

police officer on August 13, 1906. (The previous night a white woman reported being attacked by one of the soldiers.) The next

night, there was another shooting in the town, supposedly by black soldiers, though none were specifically identified in any of the

events and all of the men testified they knew nothing of the shooting.

Despite a lack of evidence or reliable testimony, all officials involved, including those of Brownsville, the U.S. Army, and

Roosevelt, merely presumed the entire unit’s guilt. A Senate Military Affairs Committee Report suggested the incident had been

staged by townspeople or outsiders to have the black soldiers removed.

the soldiers’ dismissals. The Nixon administration concurred and awarded honorable discharges without back pay.

The 24th had already suffered during a previous stay in Texas and its men were greatly dismayed at the news they were

transferring to Houston. In attempts to block the move, Battalion Commander Col. William Newman reported that, “I had already

had an unfortunate experience when I was in command of two companies of the 24th Infantry at Del Rio, Texas, April 1916, when

a colored soldier was killed by a Texas Ranger for no other reason than that he was a colored man; that it angered Texans to see

colored men in the uniform of a soldier.”

His reasoning and well-warranted protestation fell on deaf ears.

And, if he had been heeded…?

Houston deals for $2M – and trouble

The Army had planned to build 32 training facilities as it entered World War I in April 1917 and Houston’s city officials lobbied

hard to get one of the posts. Houston got its wish, two-fold, signing a $2 million contract for a sprawling 7,600-acre National Guard

training center (Camp Logan), and later, Ellington Field, as an aviation training site. Camp Logan construction and the arrival of

troops meant an estimated $60,000 a week to the Houston economy.

The caveat, for Houstonians, was that the installation came free of black soldiers, a common request for cities, especially in the

South, that sought military business. Or, as Mississippi Senator James K. Vardaman said: “Whites are opposed to putting arrogant,

strutting representatives of the black soldiery in every community.” Vardaman (an avowed racist and native Texan -- born in

Jackson County,) was among a group of Southern Congressman who unsuccessfully tried to pass legislation preventing the

enlistment of blacks to military service for the war effort.

So opposed were whites to the very sight of black men in uniform that it was not unusual for trains carrying black troops to be

fired on as they passed through Southern towns.

Whites feared the specter of armed African American men giving local blacks the appearance of equality and fomenting their own

desire for better treatment. And although many of the soldiers were from the South and used to segregation and its Jim Crow laws,

they thought their active duty service was a patriotism that would result in some semblance of civility towards them from whites,

that they would be treated better.

They were gravely mistaken.

An Army report confirmed the Houstonians view of black soldiers, concluding that both police and white citizens felt that “a

nigger is a nigger and that his status is not effected by the uniform he wears.”

On July 24, 1917, construction began for Camp Logan. Houston had gotten its military installation, and on July 28, it got 654 men

of the all-black 24th Infantry – with its all-white commanding officer group. The unit had been dispatched from Columbus, N.M. for

seven weeks duty guarding Camp Logan’s construction. Their arrival in Houston came three weeks after the most violent race war,

a massacre really, had occurred in East St. Louis, when gangs of whites roamed through black neighborhoods indiscriminately

beating and murdering black men, women, and children on July 1-3. (Some of the 24th soldiers had donated money to a fund to

help the black victims in East St. Louis.)

In striking their deal with the federal government, Houston officials had promised “in the spirit of patriotism” there would be no

racial trouble, that black soldiers would be welcomed, but the city’s whites had no such intention of opening their arms to the 24th,

regardless the length of their stay.

Chief of Police Clarence Brock, whose 159-man force (two blacks) already had a miserable reputation of brutality and other

forms of ill-treatment towards the city’s black populace, had even instructed his men to avoid using the term “nigger” when

addressing the soliders, but that edict was widely ignored as patrolmen harassed and arrested soldiers for minor infractions and

perceived slights that further increased racial tensions in a city where blacks were openly and routinely referred to as “niggers” by

police and white citizens alike.

Gradually, the soldiers began to routinely disobey the Jim Crow laws, especially when it came to public transport and the

requirement that they sit in the back of trolleys – which many of the soldiers refused to do. Their disobience and “insolence” led to

predictably harsh enforcement from police and white Houstonians hurled insults at the soldiers at every turn, as did white soldiers

and workers constructing Camp Logan.

But none were more brazen in their verbal and physical attacks than Houston policemen.

Yet, for the evening of August 23, the Houston Chamber of Commerce had planned a festive “watermelon party” to officially

welcome the black soldiers. Instead, Houston got a chaotic evening of frenzied terror it would never forget, and rarely mention.

Mutiny, riot, murder

Newman had been wary of the potential racial problems the move to Houston would present and sought to try and diffuse the

anger and apprehension over the 24th’s presence by disarming all of his men, including those whose duties were as military

policemen. Except for those standing guard duty at the camp, none of the 24th’s men were armed with nothing more than, for some,

billy clubs.

However, conditions began to boil over on August 23. That morning, patrolman Lee Sparks, whose penchant for brutality against

blacks was well known, and his partner, Rufus Daniels, had pursued a man accused of participating in a dice game. Their chase led

them to a house where they arrested a thinly clad woman and accused her of hiding the man. Outside, near the police call box, a

24th soldier approached and asked Starks what was going on and if he could get clothes for the woman.

Sparks immediately began pistol-whipping the soldier and supposedly said, “That’s the way we do things in the South. We’re

running things not the damned niggers.”

Later, that afternoon, a military policeman from the 24th, Corporal Charles Baltimore, became involved when he inquired of the

soldier’s arrest. Baltimore was also beaten by Sparks, and then shot at as he fled. He was caught, beaten again and taken to the

police station.

Baltimore would be released, however, rumors spread to the post that he had been assaulted, unjustly taken to the city jail and

possibly murdered. Incensed, a group of soldiers urged others in the unit to march on the police station, free Baltimore – if he was

still alive – and kill every policeman they encountered. There was also talk among the men that an armed mob of white citizens was

heading to the camp.

Newman’s replacement as battalion commander, Major Kneeland Snow, and his staff were never in control, though he ordered

his four first sergeants to collect all rifles and search the camp for loose ammunition, and also ordered all soldiers be confined to the

camp. Snow had confirmed Baltimore’s release from police headquarters, however, the thought that their lives were in danger from

an approaching mob became more of a concern to the soldiers who broke into the supply tent, took weapons and began firing

randomly in the dark after someone yelled, “Here they come!”

More than 100 armed soldiers, possibly led by First Sergeant Vida Henry, began their march towards the jail. Henry had, at first,

tried to prevent the men from taking arms, however, at some point joined them. In their rampage, one of their victims was a white

child who died after being hit by a stray bullet. Another victim, who may have been mistaken for a Houston policeman, was Capt. J.

W. Mattes of the 2nd Illinois Field Artillery.

Also killed was patrolman Daniels, who had been involved with the beating and arrest of Baltimore.

The men never made it to the police station. Some began to desert the march and went into hiding, others headed back to camp,

and Henry stole off on his own. He was found dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

The next day, martial law was in force and on the following day, Aug. 25, the Battalion was headed by train back to Camp

Furlong in Columbus, N.M. Once there, 118 of them were arrested and charged with murder and mutiny and were sent to the

stockade at nearby Fort Bliss in El Paso to begin their wait for court martial.

“Lord, I’m Comin’ Home”

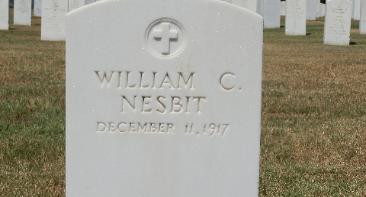

Between November 1, 1917 and March 26, 1918, the army held three separate courts-martial with the first, United States v.

William C. Nesbit, convening in San Antonio at Fort Sam Houston’s Gift Memorial Chapel, which had the only space on post large

enough to hold a trial for the first 63 men – all represented by a single attorney working on a mere two weeks preparation. (Maj.

Harry S. Grier was inspector general of the 36th Divison and had taught law at West Point, but had no trial experience and was not

a lawyer.) Their charges were: disobeying orders, mutiny, murder, and aggravated assault. All of the men entered not guilty pleas

and throughout the ordeal, even to the gallows, maintained their innocence.

Some witnesses may have been coerced into testifying against their fellow soldiers, others promised leniency or immunity, others

merely unreliable, but none of the testimony was conclusive that any of the men on trail had participated in the event. In all,

testimony was heard from 169 prosecution witnesses, but only 29 for the defense.

On November 28, 13 of the men were sentenced to be hung, however, they were not notified of their sentence until Dec. 9, two

days before their execution. For the remaining men, 41 received life sentences, four were given lesser time, and five were acquitted.

In a final letter to his family, Pvt. 1st Class Thomas C. Hawkins wrote:"Dear Mother and Father, When this letter reaches you I

will be beyond the veil of sorrow. I will be in heaven with the angels...I am sentenced to be hanged for the trouble that happened

in Houston, Texas. Altho (sic) I am not guilty of the crime that I am accused of, but mother, it is God's will that I go now and in

this way...."

Pre-dawn, on December 11, near Salado Creek, the 13 soldiers were taken to hastily constructed gallows and summarily

hung.

There had been no notice given to the media or public and their sentences and hangings would not be formally announced until

later that morning. As they were escorted to the gallows, the soldiers were reportedly calm and sang hymns.

A white soldier from Company C., 19th Infantry, which had been charged with guarding the prisoners – “the hanging detail,” it

was called – recounted the scene: “The doomed men were taken off the trucks, not one making the slightest attempt to resist. They

were shivering a little, but I think this was due more to the cold rather than fear. The unlucky thirteen were line up. The conductors

took their places and the men for the last time heard the command, “March!” Thirteen ropes dangled from the crossbeam of the

scaffold, a chair in front of every rope, six on one side, seven on the other. As the ropes were being fastened about the men’s necks,

big (Pvt. Frank) Johnson’s voice suddenly broke into a hymn – “Lord, I’m comin’ home” – and the others joined him. The eyes of

even the hardest of us were wet.”

Because the U.S. was at war, the swiftness of the executions was backed by the Articles of War. However, that did not temper

the outrage from the black community, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, but also some

military officials. Acting Judge Advocate Gen., Brig. Gen. Samuel T. Ansell, was particularly angered and said: “The men were

executed immediately upon the termination of the trial and before their records could be forwarded to Washington or examined by

anybody, and without, so far as I can see, any one of them having time or opportunity to seek clemency from the source of

clemency, if he had been so advised.”

While the NAACP began a campaign to obtain the release of the imprisoned soldiers, General Order No. 7 (which Ansell

proposed) was issued on January 17, 1918 providing that no enlisted personnel could be executed without first examination of the

trial records by the judge advocate general and confirmation of the sentence by the president of the United States.

That commuted 10 death sentences in the two other trials, but had no benefit for the 13 black soldiers of questionable guilt buried

in the far reaches of Fort Sam Houston in makeshift graves.

For the remaining two trials:

were hanged and 63 received life sentences in federal prison. One soldier was judged incompetent to stand trial. Two white officers

faced courts-martial, but were released. No white civilians were brought to trial.

Some soldiers served as many as 20 years before their release.

Conclusion

The finger-pointing for blame began immediately in the aftermath of the Houston mutiny and riot and the focus was

overwhelmingly on the black soldiers of the 24th, the logical suspects, given the event's racial overtones as well as the reality of their

actions. At best (or worst), the soldiers overreacted to the mounting tension between them and the Houston police, but there were

too many early warning signs to dismiss the event as merely an act of premeditated or even spontaneous insurrection by a vengeful

group of blacks.

The U.S. Army, the Houston Chamber of Commerce, Houston's white citizens, and especially the Houston Police Department

were all complicit in lighting a fuse that would lead to the 24th’s explosion. Most prominent among those were the police, whose

verbal abuse and thuggish arrest methods, in the end, pushed the soldiers to act as they did.

The outcome was destined. It would have been surprising if nothing had occurred during their stay in Houston.

The army was well aware they were putting the soldiers in an incendiary situation, and only had to look at the history of black

soldiers in the south and previous violent confrontations in Texas. Yet, they reasoned the 24th was the only unit available for the

duty of guarding Camp Logan construction, then gambled on sending the soldiers to Houston for seven weeks and hoped for the

best.

The Houston Chamber of Commerce and other city officials were blinded by economic dollar signs and foolishly assured the army

their black troops would be just fine in a city where African Americans were routinely disrespected and publicly demeaned by

whites, in general.

At least the white citizens were honest about their contempt for blacks, in or out of uniform. However, Chief Brock had no handle

on a brutish police force that neither liked nor respected him.

In the soldiers’ response to their abuse, there is no evidence their actions were premeditated or otherwise planned. More likely,

fueled by rumors over the arrest of Baltimore and then fear of an approaching mob of armed and angry whites, they acted out of

frustration, anger, confusion, and self-defense.

Houston’s darkest day is spoken of in hushed tones of guilt and embarrassment. The 24th has not been afforded the luxury of

silence. What happened in Houston will always be a blemish on an otherwise outstanding history – most research on the 24th at least

mentions “the trouble in Houston.” And military officials for years afterward would point to the incident as perfect reasoning, with at

least a modicum of apprehension, not to send soldiers to installations in the South. Of course, that was unavoidable, and there would

be other racially charged incidents, none the scale of what happened in Houston, involving black soldiers and white citizens – and

white soldiers(!) – in the South.

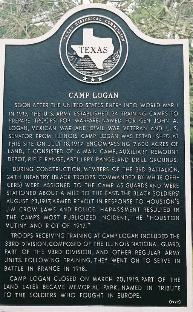

Today, the area where Camp Logan was located is called Memorial Park, a tranquil upscale area evincing but a lone marker as a

sign of the chaos that took place there 95 years ago. In May 1924, the City of Houston took ownership of the land to be used as a

park dedicated to the memory of soldiers who lost their lives serving in World War I – not to the African Americans whose careers

and lives came to a tragic end there.

Between 1934 and 1937, 17 of the executed soldiers’ bodies were exhumed from their resting place near Salado Creek and

reburied at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery. Two other bodies were released to family members. While the headstones of

graves surrounding the alleged rioters all bear formal military respect, noting name, rank, birth and death, honors, etc. Eerily, for the

Houston soldiers, their headstones depict only name and date of death.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

ONLINE SOURCES:

Infantry – a unit of the famed Buffalo Soldiers. The incident occurred on August 23, 1917, lasting roughly two hours on a hot, rainy

night, and resulted in the deaths of four soldiers and 15 white civilians. The episode has the ignominious distinction of being the only

race riot in U.S. history where more whites then blacks were killed, and it also resulted in both the largest murder trial and the largest

court martial in U.S. history.

Almost four months later, on December 11, 13 black soldiers were summarily hung at a hastily constructed gallows near a shallow

creek on Camp Travis, a National Guard training facility next to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. The men were unceremoniously

buried nearby in graves whose only identification was a number, 1 through 13. Sixty-three other soldiers were given life sentences,

and in September 1918 six more soldiers were hung at the same Camp Travis site.

There was no conclusive evidence or reliable witness testimony that any of the first group of executed men had participated in the

riots. However, the final six men were identified as having fired shots at civilians.

Historians aside, the stories of this bloody and probably avoidable event in Texas history is not well-known throughout the Lone

Star State and curiously not among most Houstonians.

History of the 24th Infantry

African American soldiers had served in the Civil War, heroically, in many cases, such as the 54th Massachusetts’ gallant

performance at Fort Wagner, S.C. upon which the movie “Glory” was based. After the war, on March 3, 1869, several all-black

units were combined into four “colored” regiments – the 24th and 25th infantries, and the 9th and 10th cavalries.

Stationed primarily at remote posts in the southwest frontier, the 24th battled outlaws and hostile Indians and protected settlers,

but served in a wide variety of other duties including building roads, constructing and repairing telegraph lines, and escorting supply

trains and mail coaches.

The unit also saw duty in Cuba, during the Spanish-American War, where they served with Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough

Riders at San Juan Hill, and the 24th would also see duty during the Philippines Revolution. Men from the 24th would be the first to

raise the American flag atop San Juan Hill.

The all-black units acquitted themselves well, so much so that 19 Buffalo Soldiers have been awarded the Congressional Medal of

Honor, including two who served with the 24th Infantry:

- Sgt. Benjamin Brown – On May 11, 1889, despite being wounded in the stomach and both arms, Brown defended a

Regimental Payroll from robbers near Ft. Thomas, Arizona in what was called the "Wham Payroll Ambush" after Army

Paymaster Major Joseph Wham who was transporting $28,345.10. - Cpl. Isaiah Mays – Along with Brown, in the same skirmish with robbers, walked and crawled two miles to a ranch for help.

from the 600 soldiers, some with families. An editorial in the Salt Lake Tribune newspaper feared drunken black soldiers would

attack “the best people of the city.” In a rebuttal letter to the Tribune, a 24th soldier wrote the men had "enlisted to uphold the

honor and dignity of their country as their fathers enlisted to found and preserve it." He also said, the men "object to being classed

as lawless barbarians. We were men before we were soldiers....We ask the people of Salt Lake to treat us as such."

And slowly but surely they would, after seeing how the soldiers comported themselves, as they joined or formed fraternal

organizations, and their chaplain, Allen Allensworth, one of only two African-American chaplains in the Army, was a popular

speaker at local churches and social events. Black and white crowds cheered for the 24th’s band and baseball teams. As the soldiers

boarded trains for duty in Cuba, whites gave them a fond farewell and expressed they would be welcomed back.

Even the Tribune acknowledged the men's general good behavior and professionalism: “By their actions these African-American

soldiers gained a measure of respect and admiration from the larger white society that was generally denied to black civilians.”

After Cuba and three tours in the Philippines, the 24th guarded supply lines in Columbus, N.M. during Gen. John “Black Jack”

Pershing’s pursuit of Pancho Villa from March 14, 1916 to February 7, 1917.

The next stop for the 24th would be Houston.

Texas fights

Some of the earliest African American soldiers in the West served in Texas, and the 24th was sent to the state at a time when the

area was considered a "soldier's paradise," with nice weather, beautiful rivers with plentiful fishing, and grassy plains that yielded

game for hunting.

While Texas might have been a paradise for soldiers and outdoorsmen, it could be a nightmare for blacks in uniform. Violence

involving black soldiers in the state was common throughout the first quarter of the 20th century. There were confrontations, most

called “riots,” with white civilians at several stops, including the madness in Brownsville at Fort Brown where the entire 25th

Infantry First Battalion was discharged without honor by President Roosevelt as a result of the Brownsville “raid.”

The soldiers were accused of conspiring to withhold evidence and identify the shooters of a white bartender and the wounding of a

police officer on August 13, 1906. (The previous night a white woman reported being attacked by one of the soldiers.) The next

night, there was another shooting in the town, supposedly by black soldiers, though none were specifically identified in any of the

events and all of the men testified they knew nothing of the shooting.

Despite a lack of evidence or reliable testimony, all officials involved, including those of Brownsville, the U.S. Army, and

Roosevelt, merely presumed the entire unit’s guilt. A Senate Military Affairs Committee Report suggested the incident had been

staged by townspeople or outsiders to have the black soldiers removed.

the soldiers’ dismissals. The Nixon administration concurred and awarded honorable discharges without back pay.

The 24th had already suffered during a previous stay in Texas and its men were greatly dismayed at the news they were

transferring to Houston. In attempts to block the move, Battalion Commander Col. William Newman reported that, “I had already

had an unfortunate experience when I was in command of two companies of the 24th Infantry at Del Rio, Texas, April 1916, when

a colored soldier was killed by a Texas Ranger for no other reason than that he was a colored man; that it angered Texans to see

colored men in the uniform of a soldier.”

His reasoning and well-warranted protestation fell on deaf ears.

And, if he had been heeded…?

Houston deals for $2M – and trouble

The Army had planned to build 32 training facilities as it entered World War I in April 1917 and Houston’s city officials lobbied

hard to get one of the posts. Houston got its wish, two-fold, signing a $2 million contract for a sprawling 7,600-acre National Guard

training center (Camp Logan), and later, Ellington Field, as an aviation training site. Camp Logan construction and the arrival of

troops meant an estimated $60,000 a week to the Houston economy.

The caveat, for Houstonians, was that the installation came free of black soldiers, a common request for cities, especially in the

South, that sought military business. Or, as Mississippi Senator James K. Vardaman said: “Whites are opposed to putting arrogant,

strutting representatives of the black soldiery in every community.” Vardaman (an avowed racist and native Texan -- born in

Jackson County,) was among a group of Southern Congressman who unsuccessfully tried to pass legislation preventing the

enlistment of blacks to military service for the war effort.

So opposed were whites to the very sight of black men in uniform that it was not unusual for trains carrying black troops to be

fired on as they passed through Southern towns.

Whites feared the specter of armed African American men giving local blacks the appearance of equality and fomenting their own

desire for better treatment. And although many of the soldiers were from the South and used to segregation and its Jim Crow laws,

they thought their active duty service was a patriotism that would result in some semblance of civility towards them from whites,

that they would be treated better.

They were gravely mistaken.

An Army report confirmed the Houstonians view of black soldiers, concluding that both police and white citizens felt that “a

nigger is a nigger and that his status is not effected by the uniform he wears.”

On July 24, 1917, construction began for Camp Logan. Houston had gotten its military installation, and on July 28, it got 654 men

of the all-black 24th Infantry – with its all-white commanding officer group. The unit had been dispatched from Columbus, N.M. for

seven weeks duty guarding Camp Logan’s construction. Their arrival in Houston came three weeks after the most violent race war,

a massacre really, had occurred in East St. Louis, when gangs of whites roamed through black neighborhoods indiscriminately

beating and murdering black men, women, and children on July 1-3. (Some of the 24th soldiers had donated money to a fund to

help the black victims in East St. Louis.)

In striking their deal with the federal government, Houston officials had promised “in the spirit of patriotism” there would be no

racial trouble, that black soldiers would be welcomed, but the city’s whites had no such intention of opening their arms to the 24th,

regardless the length of their stay.

Chief of Police Clarence Brock, whose 159-man force (two blacks) already had a miserable reputation of brutality and other

forms of ill-treatment towards the city’s black populace, had even instructed his men to avoid using the term “nigger” when

addressing the soliders, but that edict was widely ignored as patrolmen harassed and arrested soldiers for minor infractions and

perceived slights that further increased racial tensions in a city where blacks were openly and routinely referred to as “niggers” by

police and white citizens alike.

Gradually, the soldiers began to routinely disobey the Jim Crow laws, especially when it came to public transport and the

requirement that they sit in the back of trolleys – which many of the soldiers refused to do. Their disobience and “insolence” led to

predictably harsh enforcement from police and white Houstonians hurled insults at the soldiers at every turn, as did white soldiers

and workers constructing Camp Logan.

But none were more brazen in their verbal and physical attacks than Houston policemen.

Yet, for the evening of August 23, the Houston Chamber of Commerce had planned a festive “watermelon party” to officially

welcome the black soldiers. Instead, Houston got a chaotic evening of frenzied terror it would never forget, and rarely mention.

Mutiny, riot, murder

Newman had been wary of the potential racial problems the move to Houston would present and sought to try and diffuse the

anger and apprehension over the 24th’s presence by disarming all of his men, including those whose duties were as military

policemen. Except for those standing guard duty at the camp, none of the 24th’s men were armed with nothing more than, for some,

billy clubs.

However, conditions began to boil over on August 23. That morning, patrolman Lee Sparks, whose penchant for brutality against

blacks was well known, and his partner, Rufus Daniels, had pursued a man accused of participating in a dice game. Their chase led

them to a house where they arrested a thinly clad woman and accused her of hiding the man. Outside, near the police call box, a

24th soldier approached and asked Starks what was going on and if he could get clothes for the woman.

Sparks immediately began pistol-whipping the soldier and supposedly said, “That’s the way we do things in the South. We’re

running things not the damned niggers.”

Later, that afternoon, a military policeman from the 24th, Corporal Charles Baltimore, became involved when he inquired of the

soldier’s arrest. Baltimore was also beaten by Sparks, and then shot at as he fled. He was caught, beaten again and taken to the

police station.

Baltimore would be released, however, rumors spread to the post that he had been assaulted, unjustly taken to the city jail and

possibly murdered. Incensed, a group of soldiers urged others in the unit to march on the police station, free Baltimore – if he was

still alive – and kill every policeman they encountered. There was also talk among the men that an armed mob of white citizens was

heading to the camp.

Newman’s replacement as battalion commander, Major Kneeland Snow, and his staff were never in control, though he ordered

his four first sergeants to collect all rifles and search the camp for loose ammunition, and also ordered all soldiers be confined to the

camp. Snow had confirmed Baltimore’s release from police headquarters, however, the thought that their lives were in danger from

an approaching mob became more of a concern to the soldiers who broke into the supply tent, took weapons and began firing

randomly in the dark after someone yelled, “Here they come!”

More than 100 armed soldiers, possibly led by First Sergeant Vida Henry, began their march towards the jail. Henry had, at first,

tried to prevent the men from taking arms, however, at some point joined them. In their rampage, one of their victims was a white

child who died after being hit by a stray bullet. Another victim, who may have been mistaken for a Houston policeman, was Capt. J.

W. Mattes of the 2nd Illinois Field Artillery.

Also killed was patrolman Daniels, who had been involved with the beating and arrest of Baltimore.

The men never made it to the police station. Some began to desert the march and went into hiding, others headed back to camp,

and Henry stole off on his own. He was found dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

The next day, martial law was in force and on the following day, Aug. 25, the Battalion was headed by train back to Camp

Furlong in Columbus, N.M. Once there, 118 of them were arrested and charged with murder and mutiny and were sent to the

stockade at nearby Fort Bliss in El Paso to begin their wait for court martial.

“Lord, I’m Comin’ Home”

Between November 1, 1917 and March 26, 1918, the army held three separate courts-martial with the first, United States v.

William C. Nesbit, convening in San Antonio at Fort Sam Houston’s Gift Memorial Chapel, which had the only space on post large

enough to hold a trial for the first 63 men – all represented by a single attorney working on a mere two weeks preparation. (Maj.

Harry S. Grier was inspector general of the 36th Divison and had taught law at West Point, but had no trial experience and was not

a lawyer.) Their charges were: disobeying orders, mutiny, murder, and aggravated assault. All of the men entered not guilty pleas

and throughout the ordeal, even to the gallows, maintained their innocence.

Some witnesses may have been coerced into testifying against their fellow soldiers, others promised leniency or immunity, others

merely unreliable, but none of the testimony was conclusive that any of the men on trail had participated in the event. In all,

testimony was heard from 169 prosecution witnesses, but only 29 for the defense.

On November 28, 13 of the men were sentenced to be hung, however, they were not notified of their sentence until Dec. 9, two

days before their execution. For the remaining men, 41 received life sentences, four were given lesser time, and five were acquitted.

In a final letter to his family, Pvt. 1st Class Thomas C. Hawkins wrote:"Dear Mother and Father, When this letter reaches you I

will be beyond the veil of sorrow. I will be in heaven with the angels...I am sentenced to be hanged for the trouble that happened

in Houston, Texas. Altho (sic) I am not guilty of the crime that I am accused of, but mother, it is God's will that I go now and in

this way...."

Pre-dawn, on December 11, near Salado Creek, the 13 soldiers were taken to hastily constructed gallows and summarily

hung.

There had been no notice given to the media or public and their sentences and hangings would not be formally announced until

later that morning. As they were escorted to the gallows, the soldiers were reportedly calm and sang hymns.

A white soldier from Company C., 19th Infantry, which had been charged with guarding the prisoners – “the hanging detail,” it

was called – recounted the scene: “The doomed men were taken off the trucks, not one making the slightest attempt to resist. They

were shivering a little, but I think this was due more to the cold rather than fear. The unlucky thirteen were line up. The conductors

took their places and the men for the last time heard the command, “March!” Thirteen ropes dangled from the crossbeam of the

scaffold, a chair in front of every rope, six on one side, seven on the other. As the ropes were being fastened about the men’s necks,

big (Pvt. Frank) Johnson’s voice suddenly broke into a hymn – “Lord, I’m comin’ home” – and the others joined him. The eyes of

even the hardest of us were wet.”

Because the U.S. was at war, the swiftness of the executions was backed by the Articles of War. However, that did not temper

the outrage from the black community, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, but also some

military officials. Acting Judge Advocate Gen., Brig. Gen. Samuel T. Ansell, was particularly angered and said: “The men were

executed immediately upon the termination of the trial and before their records could be forwarded to Washington or examined by

anybody, and without, so far as I can see, any one of them having time or opportunity to seek clemency from the source of

clemency, if he had been so advised.”

While the NAACP began a campaign to obtain the release of the imprisoned soldiers, General Order No. 7 (which Ansell

proposed) was issued on January 17, 1918 providing that no enlisted personnel could be executed without first examination of the

trial records by the judge advocate general and confirmation of the sentence by the president of the United States.

That commuted 10 death sentences in the two other trials, but had no benefit for the 13 black soldiers of questionable guilt buried

in the far reaches of Fort Sam Houston in makeshift graves.

For the remaining two trials:

- U.S. v. Washington – December 17-22, 1917, 15 defendants, five were executed on September 7, 1918

- U.S. v. Tillman – February 18-March 26, 1918, 40 defendants, one execution

were hanged and 63 received life sentences in federal prison. One soldier was judged incompetent to stand trial. Two white officers

faced courts-martial, but were released. No white civilians were brought to trial.

Some soldiers served as many as 20 years before their release.

Conclusion

The finger-pointing for blame began immediately in the aftermath of the Houston mutiny and riot and the focus was

overwhelmingly on the black soldiers of the 24th, the logical suspects, given the event's racial overtones as well as the reality of their

actions. At best (or worst), the soldiers overreacted to the mounting tension between them and the Houston police, but there were

too many early warning signs to dismiss the event as merely an act of premeditated or even spontaneous insurrection by a vengeful

group of blacks.

The U.S. Army, the Houston Chamber of Commerce, Houston's white citizens, and especially the Houston Police Department

were all complicit in lighting a fuse that would lead to the 24th’s explosion. Most prominent among those were the police, whose

verbal abuse and thuggish arrest methods, in the end, pushed the soldiers to act as they did.

The outcome was destined. It would have been surprising if nothing had occurred during their stay in Houston.

The army was well aware they were putting the soldiers in an incendiary situation, and only had to look at the history of black

soldiers in the south and previous violent confrontations in Texas. Yet, they reasoned the 24th was the only unit available for the

duty of guarding Camp Logan construction, then gambled on sending the soldiers to Houston for seven weeks and hoped for the

best.

The Houston Chamber of Commerce and other city officials were blinded by economic dollar signs and foolishly assured the army

their black troops would be just fine in a city where African Americans were routinely disrespected and publicly demeaned by

whites, in general.

At least the white citizens were honest about their contempt for blacks, in or out of uniform. However, Chief Brock had no handle

on a brutish police force that neither liked nor respected him.

In the soldiers’ response to their abuse, there is no evidence their actions were premeditated or otherwise planned. More likely,

fueled by rumors over the arrest of Baltimore and then fear of an approaching mob of armed and angry whites, they acted out of

frustration, anger, confusion, and self-defense.

Houston’s darkest day is spoken of in hushed tones of guilt and embarrassment. The 24th has not been afforded the luxury of

silence. What happened in Houston will always be a blemish on an otherwise outstanding history – most research on the 24th at least

mentions “the trouble in Houston.” And military officials for years afterward would point to the incident as perfect reasoning, with at

least a modicum of apprehension, not to send soldiers to installations in the South. Of course, that was unavoidable, and there would

be other racially charged incidents, none the scale of what happened in Houston, involving black soldiers and white citizens – and

white soldiers(!) – in the South.

Today, the area where Camp Logan was located is called Memorial Park, a tranquil upscale area evincing but a lone marker as a

sign of the chaos that took place there 95 years ago. In May 1924, the City of Houston took ownership of the land to be used as a

park dedicated to the memory of soldiers who lost their lives serving in World War I – not to the African Americans whose careers

and lives came to a tragic end there.

Between 1934 and 1937, 17 of the executed soldiers’ bodies were exhumed from their resting place near Salado Creek and

reburied at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery. Two other bodies were released to family members. While the headstones of

graves surrounding the alleged rioters all bear formal military respect, noting name, rank, birth and death, honors, etc. Eerily, for the

Houston soldiers, their headstones depict only name and date of death.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- Austin American-Statesman, March 20, 1989.

- Houston Chronicle, July 15, 25, 1917.

- Houston Press, August 24, 25, 1917.

- Robert V. Haynes, A Night of Violence: The Houston Riot of 1917 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1976).

- Bernard C. Nalty, Strength For the Fight: A History of Black Americans in the Military (Free Press, 1986)

- Edgar A. Schuler, The Houston Race Riot, 1917, Journal of Negro History 29 (July 1944).

- C. Calvin Smith, The Houston Riot of 1917, Revisited, The Houston Review: History and Culture of the Gulf Coast , vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 85-102

- Jason Holt,“Report on T.C. Hawkins, Defendant, United States v. William C. Nesbit, Sergeant, Company I, 24th Infantry, et.al. (1979)

- Angela Holder, Camp Logan Mutiny, Houston Riot 1917 (Buffalo Soldiers National Museum)

- Martha Gruening, NAACP Investigation, The Crisis (November 1917)

- Lynn Ashby, The Riot of ’17, The Houston Post, August, 22-25, 1978

- Angela Armendariz Dorau, Of Soldiers, Racism, and Mutiny, The 1917 Camp Logan Riot and Court Martial, Heritage magazine (Spring 1998, Texas Historical

Foundation) - Army Riot at Houston Cost 17 Lives; Negro Troops Ordered Out of State; Congress Will Take Up Race Question, New York Times (August 25, 1917)

- Letter (Jan. 31, 1964), Col. Gilbert G. Ackroyd, Judge Advocate General Corps

- Emmett J. Scott, The American Negro In the World War, (Scott, 1919)

ONLINE SOURCES:

- HAIF: Camp Logan Riot/Mutiny of 1917 -- http://www.houstonarchitecture.com/haif/topic/17461-camp-logan-riotmutiny-of-1917/page__st__30

- The Historical Marker Database: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=14103

- Fred L. Borch III, Regimental Historian and Archivist: Lore of the Corps – The Largest Murder Trial In the History of the United States: The Houston Riots Courts-Martial of

- General Order No. 143, May 22, 1863; Orders and Circulars, 1797-1910; Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's-1917; Record Group 94; National Archives:

- East St. Louis Action Research Project -- Race Riot at East St. Louis, 1917: http://www.eslarp.uiuc.edu/ibex/archive/nunes/esl%20history/race_riot.htm

- Spanish-American War Centennial Web Site: Black Participation in the Spanish-American War, By Anthony L. Powell -- http://www.spanamwar.com/AfroAmericans.htm

- 9th Memorial Cavalry, Buffalo Soldiers, http://www.9thcavalry.com/

- Coming from Battle to Face a War: The Lynching of Black Soldiers in the World War I Era, Vincent P. Mikkelsen, Florida State University,

- Edsitement!, African-American Soldiers in World War I: The 92nd and 93rd Divisions,

- National Park Service, African American Heritage and Etnography, http://www.nps.gov/ethnography/aah/aaheritage/histContexts_ref.htm

- Africana Age, Schomburg Center For Research in Black Culture, African Americans and World War I, Chad Williams, Hamilton College,

- Mitra Images, Houston Riot (1917), http://images.mitrasites.com/photo/houston-riot-%281917%29.html

- Robert V. Haynes, Houston Riot of 1917, Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/jch04

| Texas Black History Preservation Project Documenting the Complete African American Experience in Texas -- "Know your history, know yourself" |

PFC. Hawkins

Daniels

Vardaman

East St. Louis Riots

Hawkins

Mays

Brown